Local helps build mask disinfectant station

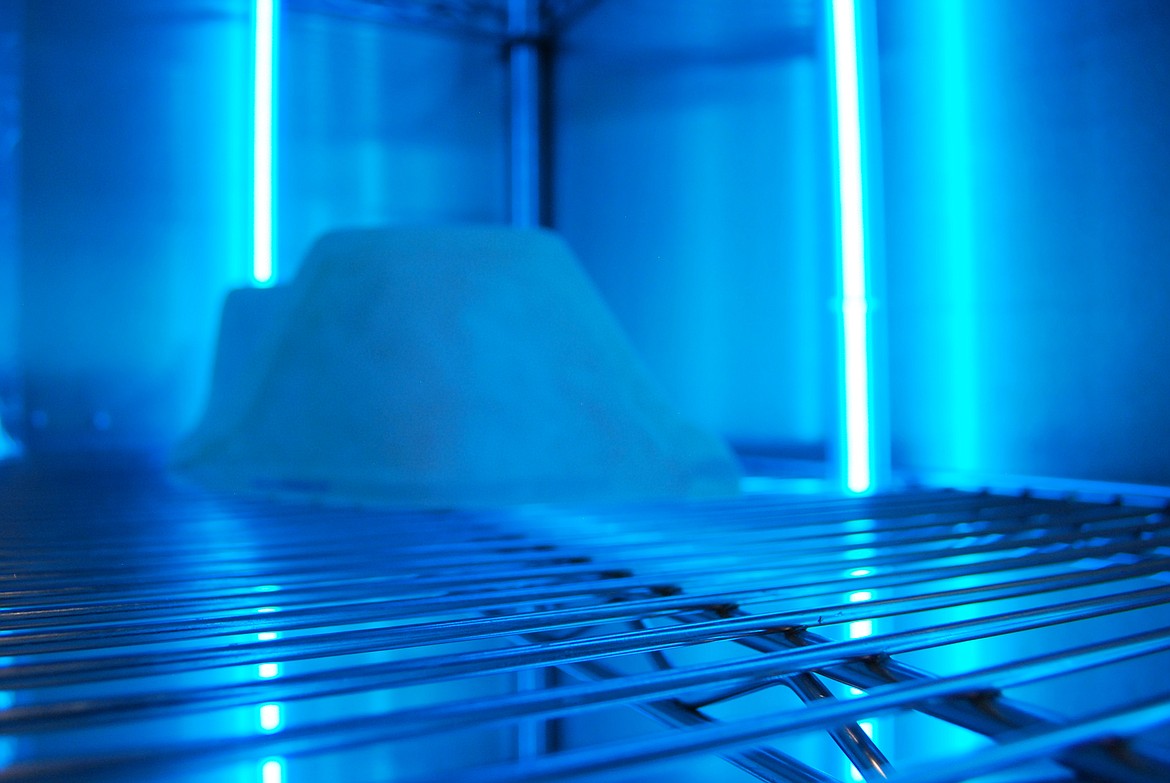

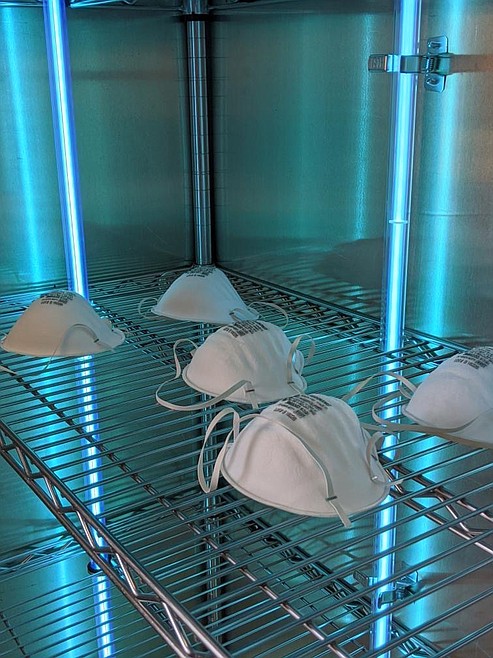

Somewhere in the confines of St. Joseph Regional Medical Center stands a one-of-a-kind mobile sanitation cabinet powered by Ultraviolet C that can clean 24 healthcare masks every 10 minutes. This cabinet was delivered on April 9 after two weeks of designing, building and validating the prototype by a team of professors and graduates at the University of Idaho, including Sandpoint native and biological engineering research support scientist Chad Dunkel.

Dunkel had been working at home for about a week when his supervisor informed him of Beasley’s health concerns. N95 masks were not being changed out daily and this was leaving doctors and nurses highly susceptible to bacteria on their 12-plus hour work shifts. Dunkel’s mission was clear — he wanted to build a disinfectant station that could use high-power UVC light to target bacteria efficiently and he wanted to construct it with easily accessible and cheap materials from the local hardware store. This way, it could be replicated by anyone.

There, standing in his indoor vegetable garden, electrical engineering professor Herb Hess had his light-bulb moment. Hess was observing his vegetables on a six-foot tall and a four-foot wide Costco rack with six shelves and casters on the bottom that allow the equipment to roll around. He proposed a similar shelving unit with reflective material and he wanted to hang light bulbs horizontally above each shelf for optimal power.

“We played with the idea of wrapping the thing in a mylar blanket, similar to an emergency camping blanket, but the wavelength of light passes right through mylar,” Dunkel said. “I proposed building it out of something more rigid and out of a material that does indeed reflect a good portion of UVC light.”

It turns out aluminum was the perfect candidate, with a greater than 80 percent reflective rate. University of Idaho’s machine shop quickly cut the team some panels of thin aluminum sheeting to build the shell of the cabinet and finished the prototype with two double doors in the front.

The prototype underwent multiple design changes to accommodate the power and materials available to them. On day two of design the team had hit a major roadblock — sourcing UVC bulbs. These bulbs were rare finds because they kill bacteria and viruses, a necessity for businesses all around the world right now.

“Most places online are backordered or sold out completely and if we could find them, the shipping was going to take upwards of a month, so we were kind of grasping at straws,” Dunkel said. “Luckily, we got in touch with a project engineer that works in Lewiston at the wastewater treatment facility and he indicated to us that they had decommissioned an old DEC (Department of Environmental Conservation) wastewater disinfection system and they had a bunch of old and brand new bulbs sitting around that they were willing to donate to us.”

The team’s target goal was to reach 1 Joule per centimeter squared of UVC power in the cabinet. This roughly translates to one-fourth of the power used for a traditional microwave.

“Based on publications and prior research, that should be enough to kill any COVID-type virus and anything else for that matter,” Dunkel said. “The numbers are a little more robust because it’s bacteria, but ideally we are killing everything.”

However, Dunkel said a major priority for the team was building a system with safety measures in place to fully harness the UVC light. Because this light can be harmful on human skin and eyes, the machine is only programmed to power on if the unit is completely enclosed.

“It’s a short wavelength that’s invisible to the human eye but still does a lot of damage,” he said. “I like to think of it as staring directly into the sun all day, but it happens in a matter of minutes.”

According to Dunkel’s calculations, this cabinet will last at least 12,000 hours of continuous operation before the UVC bulbs need to be changed out, which should last for the duration of the pandemic. Dunkel plans to keep up with light intensity readings to give health care officials peace of mind.

Many commercial disinfectant stations exist for large populations and wealthy communities, but none exist at this caliber. “Because there really was no need before, these things were pretty small and you could only do a mask or two at a time,” Dunkel said. “Ours is a little more high intensity and a larger scale so they can disinfect a lot more in a single short duration.”

There is potential for this sanitation system to exist post-pandemic and do more than just sanitizing masks, Dunkel said. These cabinets could be designed to disinfect gowns, face masks, face shields or gloves, but it all depends on the return of strict certification on medical products.

“A lot of those restrictions have been dropped because we are in such dire need,” Dunkel said. “Pretty much any medical facility is willing to take whatever they can get, because whatever they can get has got to be better than nothing, but I certainly think there could be applications down the road.”

By the end of the week, Dunkel hopes to publish an open source document for anyone who would like to try and build a sanitation cabinet on their own. Other professors are working to provide several parallel designs, including a package to build a sanitation station out of wood, which would cut cost and be more achievable for people who don’t have access to a machine shop for cutting aluminum sheets.

The University of Idaho has even offered to ship certain materials, such as the UVC bulbs for free of charge.

“Anyone who wants to build these cabinets but might not have access to the bulbs, we are more than happy to donate bulbs and quartz sleeves and ship them directly to them,” Dunkel said.

With numerous donations for local stores and shops, the first prototype cost about $800. In comparison Dunkel estimated commercial use of sanitation systems to cost a few thousand dollars.

“The rack itself was about $100, which I actually donated from my house, so we were able to cut costs that way,” he said.

The design team is looking for donations of materials or places to harvest products for cheap. Dunkel plans to start constructing cabinets for Kootenai Health in Coeur d’Alene, and potentially Spokane in the upcoming weeks.

In the meantime, his team is answering questions and accepting building requests on the University of Idaho Engineering’s website.

Dunkel is a class of 2006 graduate from Sandpoint High School. He wanted to let Bonner County know that him and his team are ready to help the community in any way possible.

“Whether it’s 3-D printing masks or sterilizing equipment, we are certainly trying to help anywhere that we can and Sandpoint is close to my heart,” Dunkel said.

Aly De Angelus can be reached by email at adeangelus@bonnercountydailybee.com and follow her on Twitter @AlyDailyBee.