Move unearths buried treasures

COEUR d’ALENE — As a Nov. 16 crowd of local lookie-loos watched a semi truck haul the J.C. White House to its new home near the base of Tubbs Hill, a team of local historians swapped their curiosity caps for their Indiana Jones fedoras.

The archaeologists spent the day living every history buff’s dream: Exploring a freshly-excavated discovery from an ancient ruin.

“We recovered some beautiful pieces,” said Jocelyn Babcock, development director for the Museum of North Idaho. “We were really excited about their condition.”

Babcock said once the White House left its Sherman Avenue address — the iconic home’s familiar perch for the past 116 years — explorers found a local treasure trove of artifacts. The remains of the White House lore do more than provide curios for pawn shops: Museum officials say the artifacts will help better understand the early days of Coeur d’Alene’s boom.

“One of the coolest things we found was the mortar ball,” John Swallow, CEO of New Jersey Mining and one of the men responsible for physically moving the White House to its newest locations, told The Press.

The mortar ball was found beneath the White House porch after the move, buried in shallow dirt.

“From what I understand,” Swallow said, “Alfred White was the son of J.C. White. But his dad’s initials were also A.W. The story we like to tell — the one we like to think about — was that the son was sitting on the porch one day, made the ball, carved his name into it and tossed it under the porch.”

“To be honest,” Babcock said, “we were expecting [to find] a little more, based on the age of the house. But the things that were found were rather surprising.”

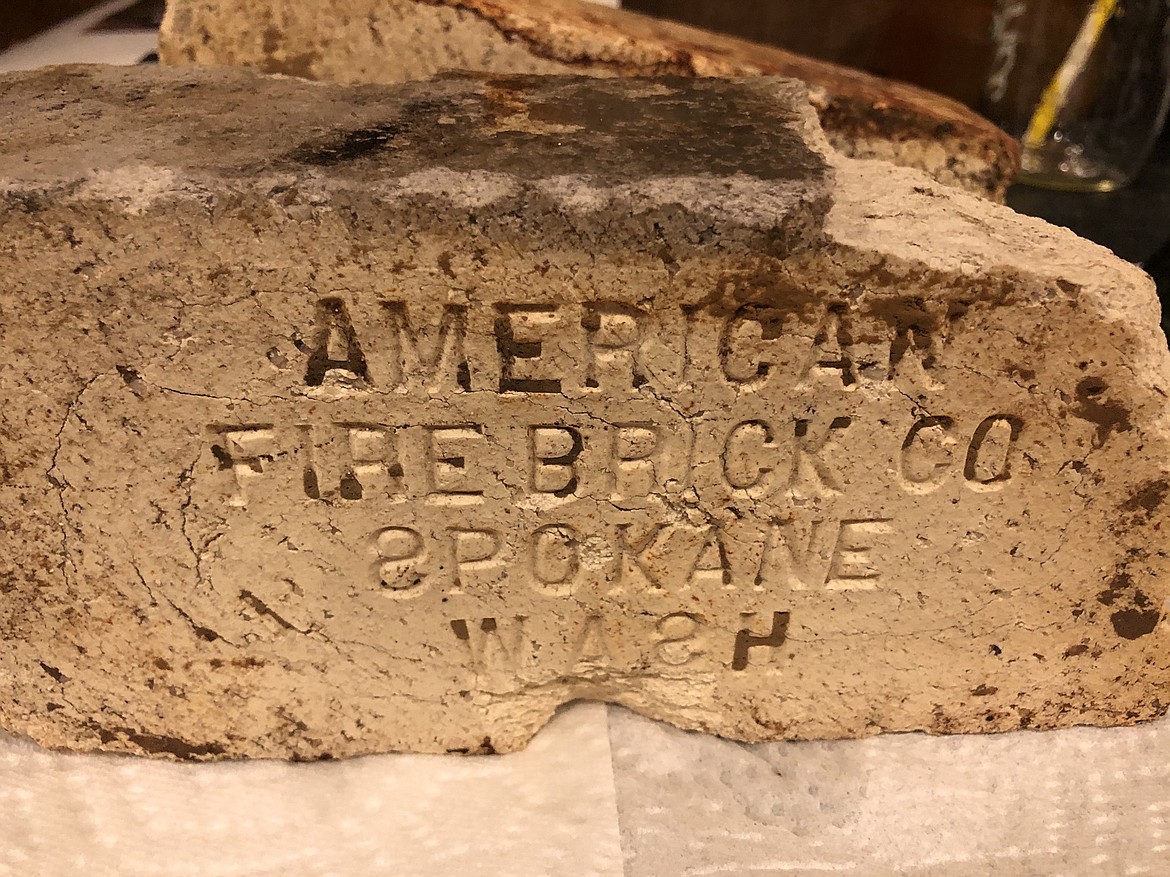

Those recoveries include glass containers — which historians believe might be a spice jar and an inkwell — a mortar ball, shards of broken china, an old horseshoe and a pair of bricks from the fireplace. The bricks were found in the remains of a fireplace that had been torn out long before the move, with American Firebrick Company, the Spokane masonry company, carved in the stone.

The American Firebrick Company, according to Swallow’s research, was founded in Spokane in 1902, one year before the J.C. White House was built.

“So the bricks used in the White House were some of the first bricks this company ever sold,” he said.

“That brickwork was so interesting,” Babcock agreed. “If you look at it closer, the ‘S’s are backward ... We don’t know why.”

Not yet, anyway. Babcock said Museum staff will evaluate the artifacts for clues that might help historians paint a clearer picture of Coeur d’Alene’s past. The J.C. White House is one of the last original homes in the area. Built in the wilder heydays of Coeur d’Alene’s infancy, its continued presence on Sherman Avenue represented a bridge between the past and the present. Now, as staff and organizers prepare to one day open the White House as the new Museum of North Idaho home, they plan for the historical legend to eventually become a bridge between the past and the future.

To do that, however, Babcock stressed there’s plenty of work still to be done.

“We do need to winterize it, first and foremost,” she said. “We were in kind of a hurry-up-and-wait mode for a while. We were kind of waiting for [the White House] to arrive, and it was worth the wait. But now we need to winterize it and do some minor repairs.”

Some of those repairs were the result of a nerve-wracking, 11-block move.

“We definitely had a little bit of damage from [brushing against] the trees,” Babcock said. “What we were really looking out for was the release [from its reinforcement beams]. They had to install some wood on the walls and brace the walls for the move. They had to reinforce the beams. And the house needed some work anyway. We’ll obviously do some interior and exterior renovations. We’re rebuilding the porch because it was a characteristic everyone enjoyed.”

She added that all things being equal, the house survived the move in great shape.

“The paint got a little scratched up in places,” she said. “I think we lost a little piece of the roof. But it needed a new paint job. It needed a new roof. What I was really worried about were the windows: I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, please don’t let any of those windows break.’ Those windows have some gorgeous craftsmanship to them. So I was very happy when it was over.”

One of the mysteries of early 20th century Coeur d’Alene culture was one Babcock said she already knew but never thought about until helping prepare to turn the White House into a museum.

“It only has one bathroom,” she said. “All those bedrooms, and they only had one bathroom ... So we have to install some public bathrooms on both floors ... And the building doesn’t have any heat, not in the galleries. We have some [heat] in the office spaces, but we obviously can’t open unless we get the heat going. As we’ve learned these past few months, it can get cold here in North Idaho.”

While moving the historic house was an attempt to hold onto Coeur d’Alene’s past, organizers recognize they’re pressed with a demanding future. Museum staff is required to occupy the space by December 2020. Babcock said the current timetable is to have a fully functioning realization of the Museum’s new home by January 2023.