Veteran recalls World War II, Korean service

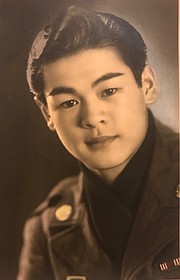

At 95, George Dong of Sandpoint is one of our country’s few surviving World War II veterans.

Dong served in the 411th Field Artillery in the European Theater, stationed in England and Germany. He was one of the approximately 20,000 Chinese Americans who served. Later, he served stateside with the Army National Guard during the Korean War.

Dong was scheduled to receive the Congressional Gold Medal in September, but the honor ceremony has been postponed due to the pandemic until further notification.

“I was with two of my friends (in San Francisco) where we saw a big billboard advertising the Signal Corps. You had to have 2.5 years of college or pass a test. I took the test and passed, and we headed to Fresno, but I was too young, they said.”

While waiting to turn 18, Dong worked at a chicken ranch devoted to producing food for soldiers. “I graded the eggs and trained a German Shepherd to be gentle with the chickens. No one ate a fresher egg than me,” he said. He would catch eggs in his hands as they were laid by hens.

Dong was born in San Mateo, California and grew up in San Francisco during a time when Chinese Americans experienced prejudice. “In those days as kids, we were confined to certain areas because we were Chinese, he said.

“We couldn’t cross Powell and Broadway or Kearny and California streets,” he said, due to the gangs lined up to stop them.

“I would face the leader or the one standing next to him. I stood up to them. My oldest brother stayed away from everything. My second oldest brother was not capable of standing up to them. I was always fighting. There were restricted areas, but our school was through the restricted area. Finally, they put a police car on every block, and that stopped it,” he said.

As a child during the Depression, he had to help his parents, who worked as farmers. “I did the washing. I had to carry soaking wet sheets up three flights of stairs to hang them on the roof,” he said, adding that sometimes they didn’t have food. “The school would bring us graham cookies and milk for a treat,” he said.

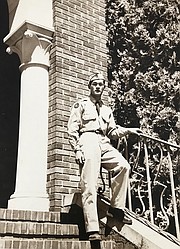

Finally turning 18, Dong joined the U.S. Army in 1944. He underwent training at Fort Lewis, Washington before traveling on a troop train for more training in North Carolina. He is grateful for that experience. “I got to see the United States because we got off the train to do calisthenics every day,” he said.

After training, Dong was sent to North Wales on the U.S.S. Argentina. On board was comedian Mickey Rooney “He was a riot,” he recalled.

Dong was stationed in a most beautiful place in North Wales, where the book and subsequent 1942 Oscar-winning movie “How Green Was My Valley” were set. “You could actually see the wind—it whipped back and forth in the tall grass,” he said. The people there were very good to us; they gave us food “charging us just one penny,” he said, “because we were there to keep them safe.”

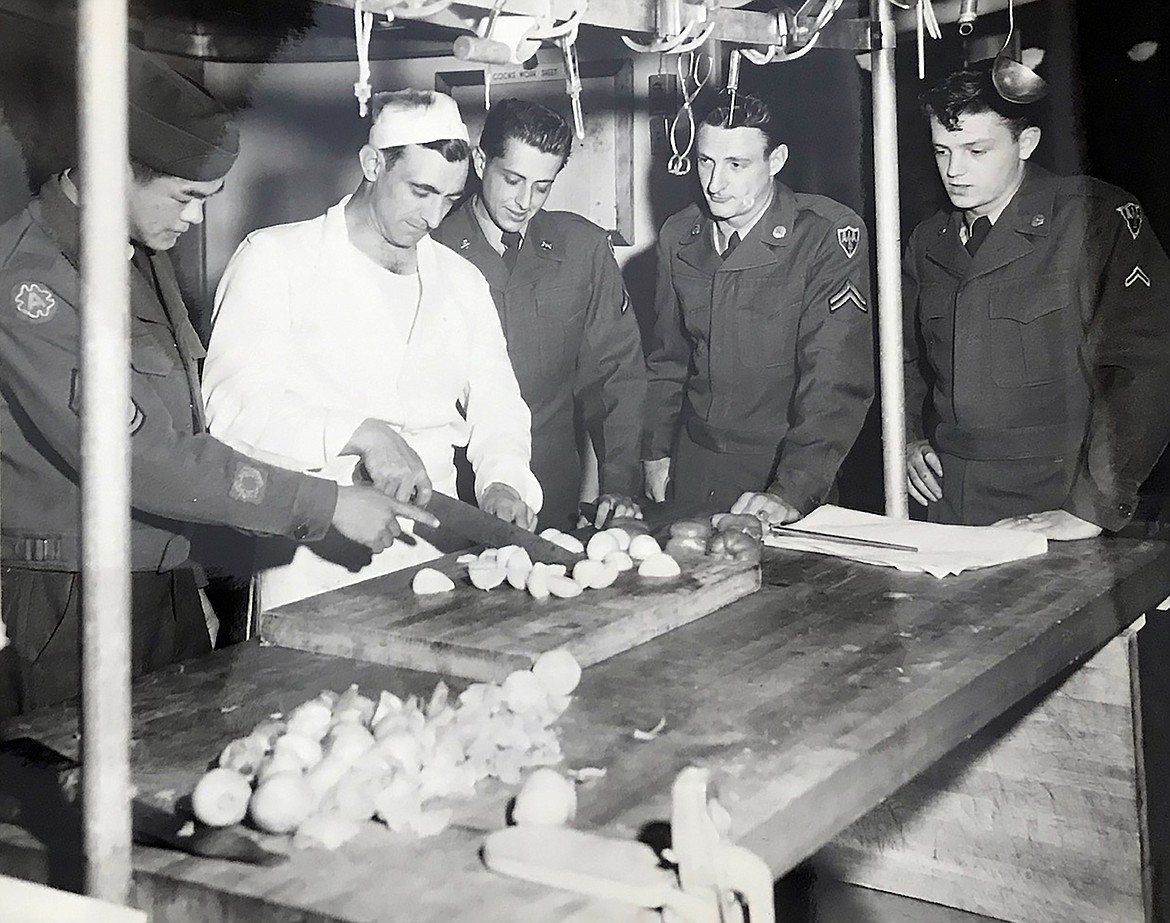

Sergeant First Class Dong was sent to England and to Germany. He ran mess halls and received a citation from the group headquarters for making the food-serving process more efficient. He said it was a difficult job because so many of the servicemen were hillbillies who were always drunk.

Dong was at the Elbe River in Germany when German soldiers swam toward the American side rather than be captured by the Russians. On his Congressional Gold Medal tribute page, it says: “Although the Elbe River was not wide, the water was swift and cold and many German soldiers carrying heavy packs were swept away. Once on shore the German soldiers were searched with fixed bayonets to identify SS officers.”

At the Battle of the Bulge, where Hitler’s soldiers attacked in freezing rain and deep snow drifts, some 100,000 Americans were killed, wounded, or captured during this, the bloodiest battle of the war, which covered an 80-mile stretch on the borders of Germany, Luxembourg, and Belgium. It started on Dec. 16, 1944 and ended Jan. 25, 1945. Taking a big risk, Dong went there to visit his brother, Fred, who was also in the Army.

“There were hills of human bodies there,” he said, adding, “I am lucky to be here today.”

After his honorable discharge in May 1946, Dong returned to San Francisco where he worked for the Dean Witter and Co. until the Army National Guard called. Dong had signed up for the Guard at the encouragement of his brother, Fred, who told George he could keep the rank he had in the Army, make money, and show up just once each month. But what happened instead was the Korean War. The Dean Witter Company paid him while he served in the Guard stateside, working in defense in case of an attack on U.S. soil.

Dong married his wife, Laura Sam in 1949, and his daughter, Delia, was born in 1953. They were married until she passed away in 2016.

He continued working for Dean Witter & Co. as a purchasing agent until his retirement, but in the interim pursued many other interests, as well.

As a Daoist or Taoist Buddhist, Dong was concerned about the young people in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco in the 1960s. He created a temple to teach discipline and respect through martial arts.

He had started with karate, and then transitioned to Gung Fu and Xi Gong and then Tai Chi. He was able to perform energy healings and spent many hours in standing meditation. He became a Tai Chi master.

“My dad has a sensitive spiritual side,” said his daughter, Delia (Dee Dee) Freney, with whom Dong lives on the Pend Oreille River near Laclede, along with Dee Dee’s husband, and Dee Dee’s auntie, who recently moved in.

“In Chinatown, people would come up to him and honor him with an open hand to fist and a bow, she said.

“My dad finds energy in trees and in crystals,” she said, adding that he has excelled in photography, fishing, and he speaks Cantonese fluently. He is an expert in writing with Chinese characters.

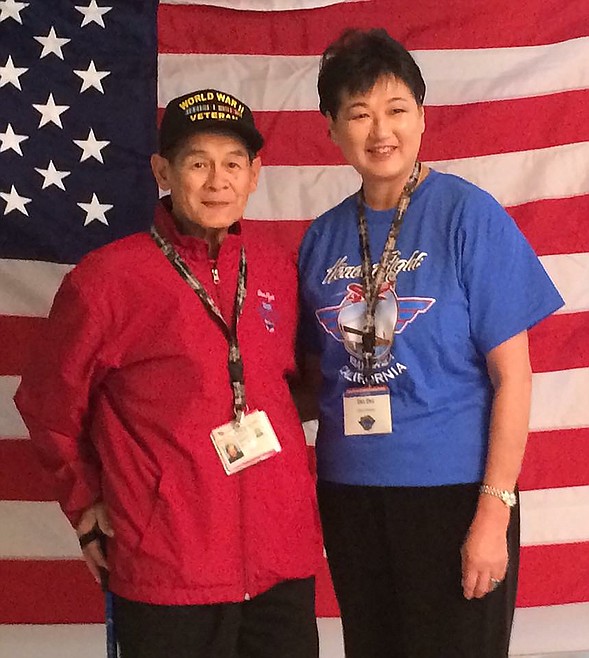

In 2017, Freney took her father on his birthday on the Honor Flight to Washington, D.C., where they were greeted by two fire engines shooting water and by many people who held signs in the airport welcoming the veterans. They were able to tour the WWII Memorial, the Korean Memorial, the Lincoln Memorial, the Martin Luther King Memorial, and the Vietnam Memorial.

Dong attributes his long life to his Eastern philosophy, being in touch with nature, and to his secret Chinese liniment, or salve, for external ailments.

“You have to be on the right side of the track,” he said. “I took the straight and narrow path. You have to take opportunities to help others, and do the right thing, he said.

“Also, you have to have the right kind of soy sauce, and beer, root beer, that is!”