Housing challenges worsen

▶️ Listen to this article now.

COEUR d’ALENE — There were some clear takeaways from findings of the latest look at the local housing market.

Little has changed in the past year.

Home prices are high. So are rents.

Demand is very high. Inventory is very low.

Newcomers are arriving all the time. Workforce housing is shrinking. And locals are priced out, forced to leave the area.

“This is kind of grim, right?” said Maggie Lyons, executive director of the Panhandle Affordable Housing Alliance.

Lyons, Coeur d’Alene City Councilwoman Kiki Miller and Gynii Gilliam, executive director of the Coeur d’Alene Economic Development Corp., all with the Regional Housing and Growth Issues Partnerships Group, presented a housing update to the City Council on Tuesday, based on their work over the past 14 months.

They offered some hope and possible solutions.

The group’s mission is for home ownership to be achievable for residents of Kootenai County, and to build and retain housing inventory for local workers

But that's growing more difficult.

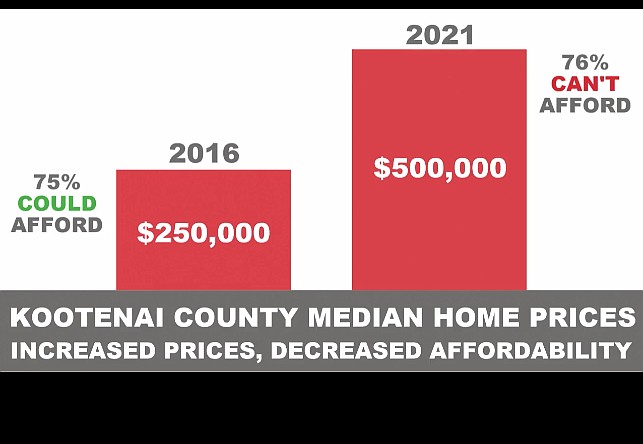

Five years ago, 75% of county residents could afford a home when the median price was $250,000.

Today, according to the Coeur d’Alene Association of Realtors, the median price is $520,000.

Lyons said the affordability gap is growing. The median household income in Kootenai County is $65,500. But to buy a $500,000 home requires a median income of $100,000.

“This picture gets worse as mortgage rates go up,” Lyons said.

More than half of county residents can’t afford the average monthly rent of $1,400, and rent rose about 30% in the past year.

That's forced some with middle-class incomes, a good job, to either leave the area, move in with relatives, or quit working and seek government subsidized housing.

“Many found themselves homeless for the first time in their lives because the rental became so valuable they were sold,” Lyons said.

More homes are needed in the $200,000 to $350,000 range, but Lyons said that according to the Coeur d’Alene Multiple Listing Service, there were only 30 Kootenai County homes currently for sale for under $500,000, and 17 of those were manufactured homes on leased land.

The trend is not expected to change.

Idaho was the fastest-growing state in the nation from 2010 to 2020, with a 17% population increase. Kootenai County’s population rose 24% in that time.

“We have the silver tsunami of people moving in here,” Miller said. ‘We need to be proactive right now to start preserving this inventory.”

She said of those acquiring homes here in the past two years, more than 50% bought either second homes, investment properties or were retirees.

“That ate up a huge amount of our inventory in 24 months,” she said.

Lyons said the area has a 2,350 housing unit deficit that is growing.

All of that negatively affects quality of life, Gilliam said.

It means jobs go unfilled, new businesses won’t come here and old ones leave, and kids growing up here won't be able to stay. The study found it translates into $159 million in lost wages and the loss of $220 million in Gross Regional Product.

“We know that a healthy housing infrastructure reflects the needs and the incomes of the people that live in the community,” Lyons said.

There is a chance to change the trajectory, Gilliam said, but the solution won’t come from government alone.

The Regional Housing and Growth Issues Partnerships Group has been in contact with other cities to try and copy effective methods tackling the lack of affordable housing.

It has communicated with developers, builders, real estate agents and property owners to discuss land trusts, housing trust funds and creative housing, such as putting two or three smaller units, perhaps a townhouse, on a property instead of one larger house.

It's looking at private and public partnerships and tax credits, and reaching out to property owners who will work with nonprofits for low-income housing.

They're also encouraging employer-funded housing and what is called “HomeShare,” a national template that links empty nesters, perhaps with a bedroom/bathroom situation downstairs, with those needing reduced rent.

“That could create a huge amount of inventory and support our seniors at the same time,” Miller said.

“Density flexibility” was mentioned while maintaining the character of neighbors.

“We have land and density opportunities if we’re creative,” Miller said.

Miller talked of policies that protect and create housing for local workers, seniors and the disabled.

“We can’t control demand, but we can control supply, as a community,” Lyons said.

The 49-unit “Culver’s Crossing” development in Bonner County targets low-income housing. It includes income restrictions and prior residency requirements of at least two years.

“I think it’s an exciting model for us to just copy here,” Lyons said.

But time is of the essence.

Miller said she's called many cities and most say, “We did too little, too late."

“It’s really affecting everyone around the country. So, we’ve got some policy work we need to do.”